The Silk Road in Iran and the Persian Caravanserai

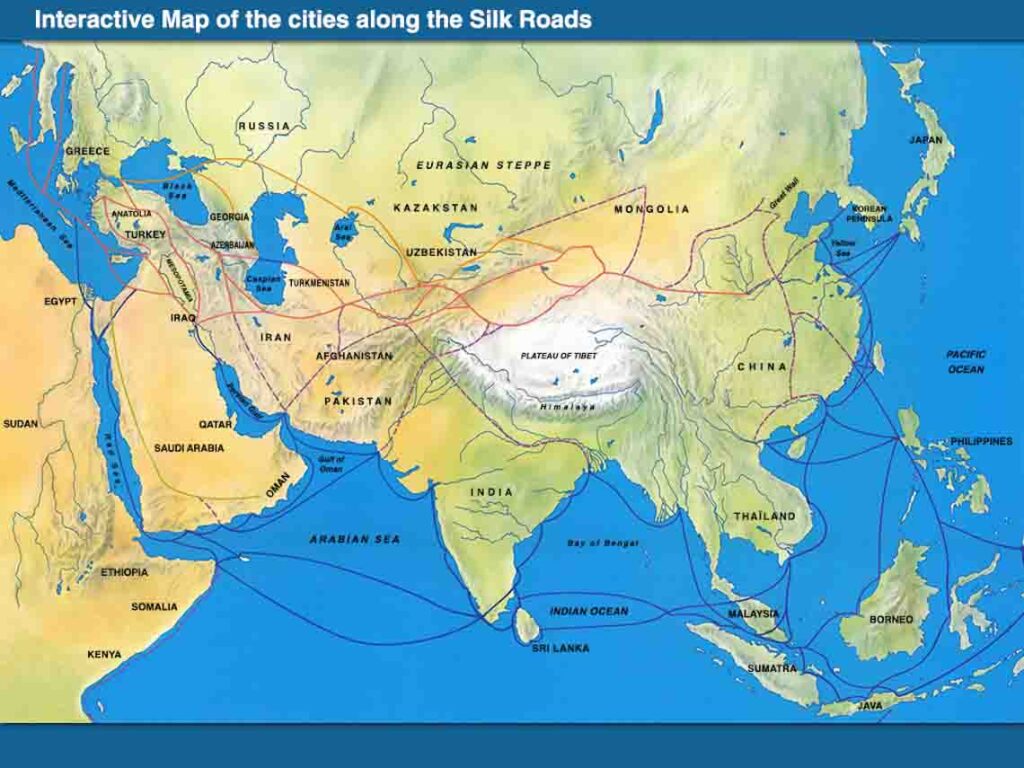

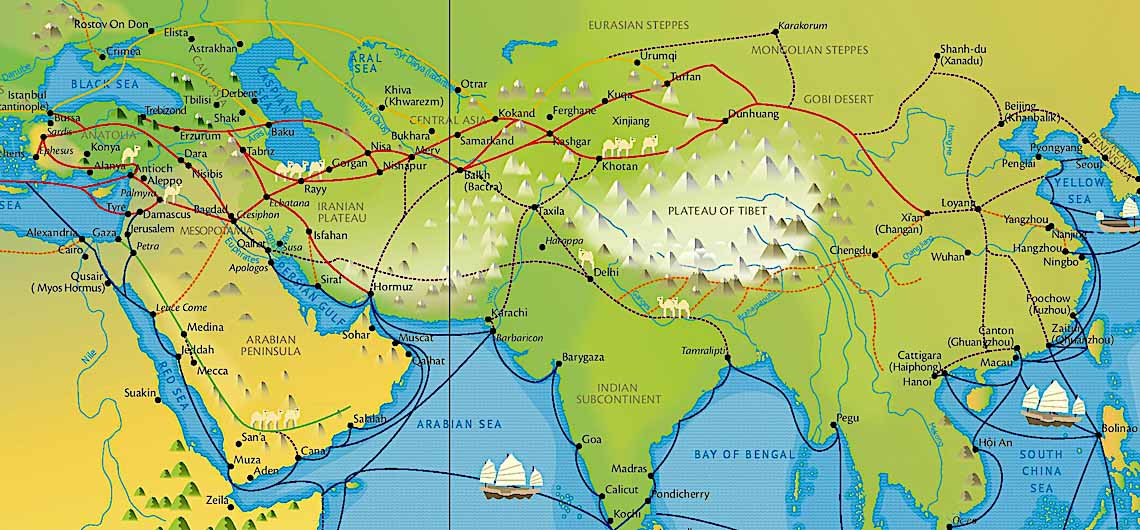

The Silk Roads, as the oldest trading and communication network across the world, have connected many civilizations for millennia, bringing together peoples, cultures and economies. The roads provided a ground not only for the exchange of goods but also for the interactions of ideas and cultures that have shaped a part of our world today. The people living along the Silk Roads enjoy diverse cultures, religions and languages, and as a result of their interactions, they have influenced each other.

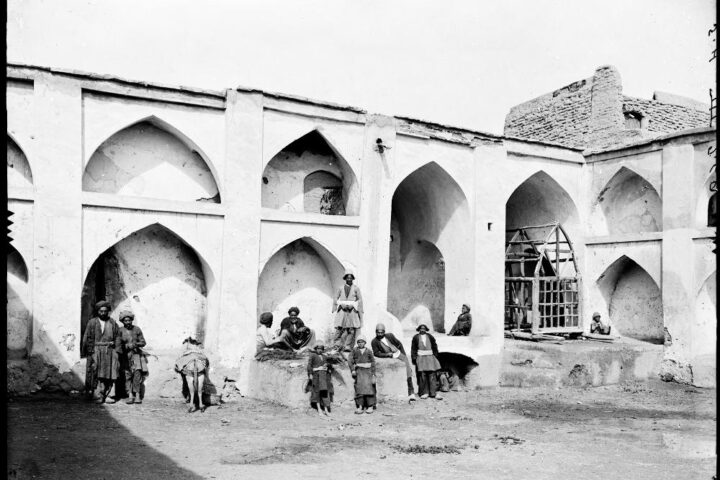

The Silk Roads have created architectural elements related to their functions, which reflect regional techniques, arts and even beliefs. Such elements include caravanserais, navigation towers, water cisterns, qanats, mosques and even cities. The caravanserais in particular functioned as meeting points for travellers and places for merchants to conduct their business, trading goods and commodities. Furthermore, they were a place for scientists and many other scholars to exchange their knowledge and ideas. Such places could make it possible to discover new civilizations or to learn new languages.

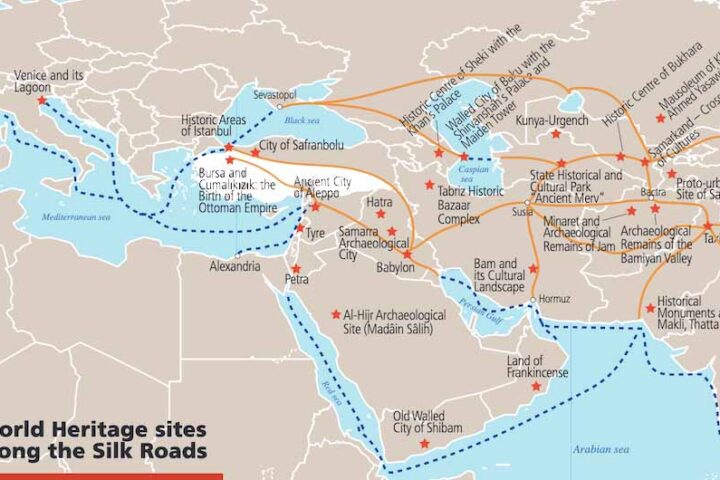

Today, many historic buildings and monuments still stand, marking the passage of the Silk Roads through caravanserais, ports and cities. But the long-standing and ongoing legacy of this remarkable network is also reflected in the many distinct but interconnected cultures, languages, customs and religions that have developed over millennia along these routes.

Precious silk

Even though a variety of valuable materials, goods and commodities were transported, sold and traded along the Silk Roads – precious stones such as agate and turquoise, spices, salt, medicine, jewellery, etc. – it was silk that captivated Western markets and civilizations from antiquity until the end of the 19th century. The reason behind the huge demand for silk went beyond its superlative quality and extensive use in the production of luxurious clothes and fabrics. Its popularity was also linked to the mystery that shrouded the production and processing techniques of silk in the East and elsewhere.

Silk consumers in the West did not know where silk came from. They knew only that it arrived from the Far East. They were always trying to discover the secret of producing silk in order to make it themselves, without having to pay a lot of taxes. Several expeditions were organized to find out where silk originated but all of these maritime quests failed.

Tracing the Silk Roads in Iran

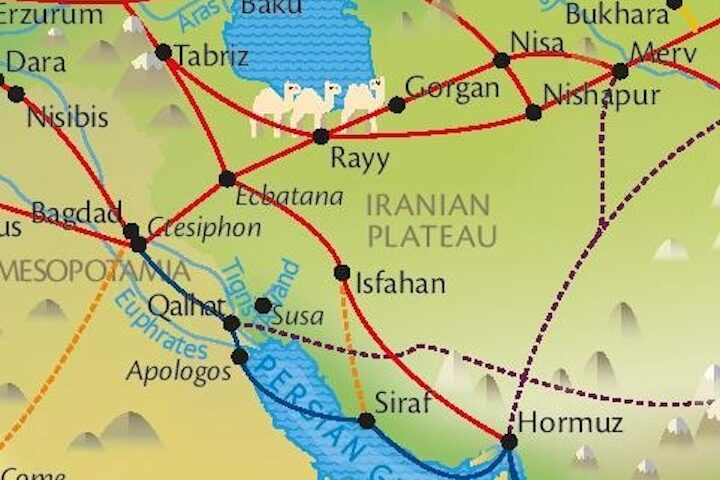

According to historical records, the first road to be excavated and researched was the Persian Royal Road dating back to the Achaemenid period. We know the first architectural elements constructed along this road rendered services to the royal messengers and stewards. These buildings were named chaapaar xane and they were the earliest prototype of caravanserais. Herodotus too mentions stations along what we now term the Silk Roads that might have been caravanserais.

One of the earliest historical documents that tell us about the road’s geographical direction, and the stations where the caravans and merchants stayed, is a book called The Parthian Stations by Isidore of Charax. It maps the road in detail from the western borders of Iran to the eastern part of the country. The reader can find the location of the first caravanserais and see the geographical situation of the roads connecting the western Iranian localities to the eastern ones. The book provides the first conclusive evidence of caravanserais existing and operating along the Silk Roads.

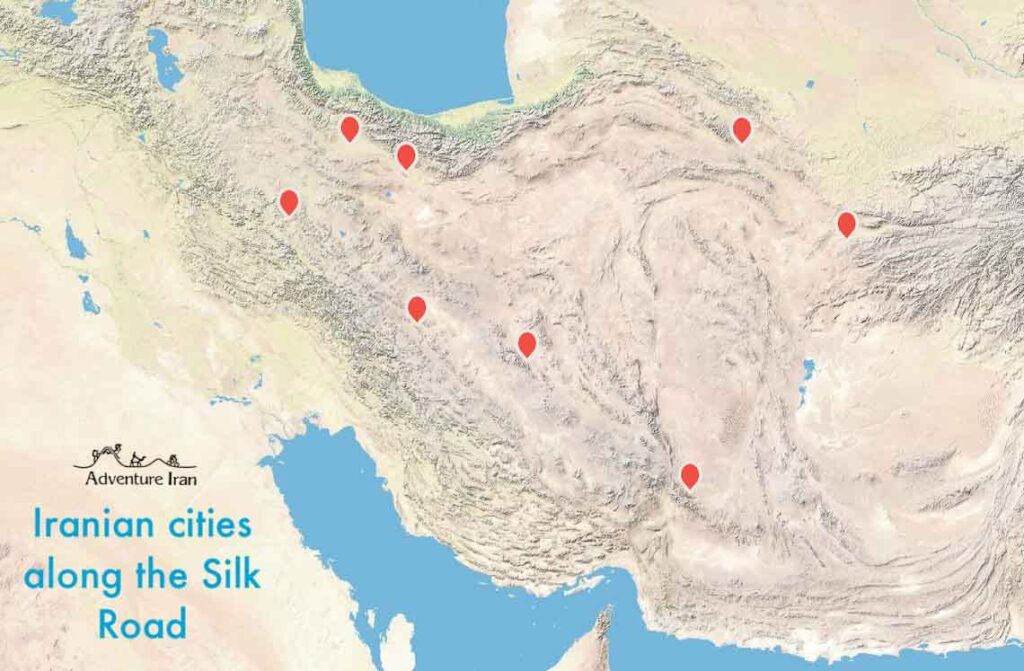

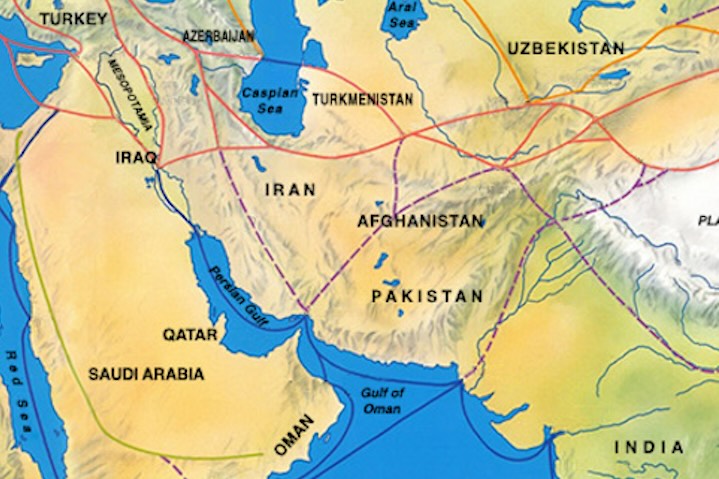

The original name of the historical road in Iran that we now include in the Silk Roads was Shāhrāh-e Khorāsān. The main branch of the Silk Roads enters Iran through the eastern border with Turkmenistan, connecting Merv to Neyshabur, and then goes westward to Rey, now called Tehran. From Tehran, there are two branches: the southern one goes to Iraq and Syria, and the northern one heads northwest to Turkey and Constantinople. The four focal points in the Iranian part of the Silk Roads are Neyshabur, Tehran (Rey), Hamadan and Tabriz. All of these cities were the capital of Iran in different periods.

A chain of caravanserais

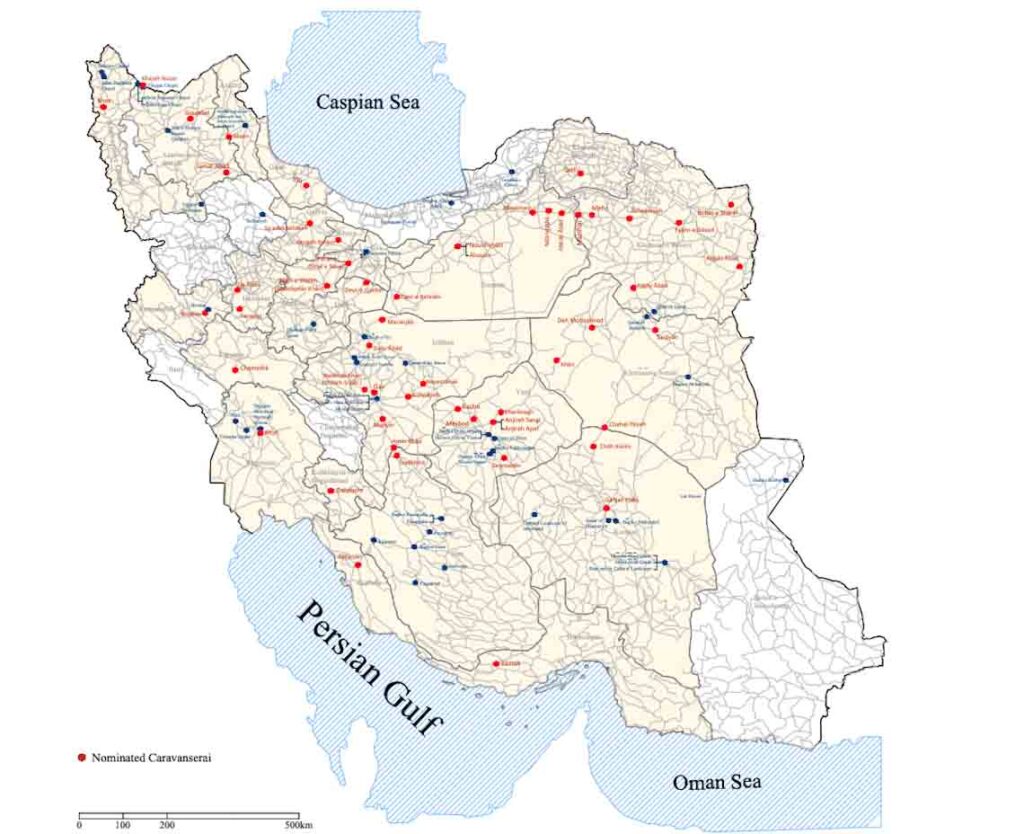

According to recent studies, caravanserais were spaced out according to the distance that caravans can travel within a single day. That is why every 30 to 40 kilometres, i.e. the maximum a caravan can advance per day, a caravanserai was built.

The caravanserais differ in design, material and geographical location. Some were made of fired bricks, some of stone, and some of a mixture of both. The materials varied according to the caravanserai’s site and its climate. Caravanserais are not evenly distributed across the Iranian part of the Silk Roads – many caravanserais can be found near the big cities and bazaars, while those situated in deserts and mountainous regions form a chain maintaining the standard distance. There are more than 100 caravanserais across the Iranian part of the Silk Roads, constituting one-fifth of all existing caravanserais in Iran. Many stayed in use until the industrial revolution, when steamships were invented. A number of these structures are barely standing and under restoration, but a few have already been restored and rehabilitated as travel accommodation.

IRAN World Heritages related to the Silk Roads

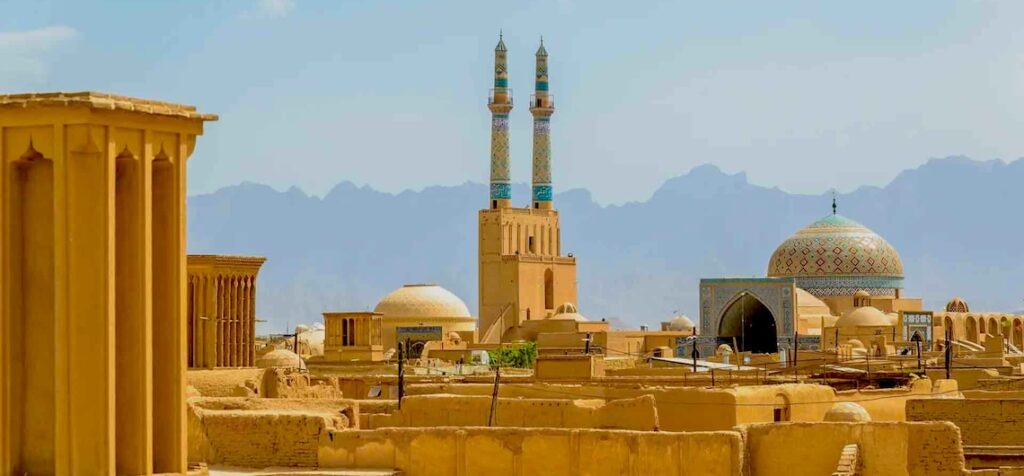

In addition, there are several World Heritage sites in Iran that are related in various ways to the Silk Roads, including the Tabriz Bazaar, Persian Qanat, Persian Garden, Gonbad-e Qabus (tower), Golestan Palace, Bam cultural landscape, Bisotun, Persian Caravanserais and even the city of Yazd.

The Historic City of Yazd was inscribed on the list of a World Heritage Site in 2017.

A number of properties linked to the Silk Roads have been put on the Tentative List; among them are Tous historical site, Qazvin Bazaar, Damghan Mosque Tarik Khaneh), and Neyshabour historical city.

Kharanaq, Meybod and Naeen (Naiin) are other historical towns which were on the various routes of the Silk Road.

“In September 2023 UNESCO registered Persian Caravanserai on the list of World Heritage Sites.”

Regarding intangible cultural heritage, Iran has several elements inscribed on UNESCO’s Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage that are directly or indirectly related to the Silk Roads, and a number of other elements have been nominated. Those inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in recent years are Nowrouz; Art of crafting and playing with Kamantcheh/Kamancha, a bowed string musical instrument; Flatbread making and sharing culture: Lavash, Katyrma, Jupka, Yufka; Traditional skills of building and sailing Iranian Lenj boats in the Persian Gulf; Ritual dramatic art of Ta‘zīye; Pahlevani and Zoorkhanei rituals; Music of the Bakhshis of Khorasan; Radif of Iranian music; Traditional skills of carpet weaving in Kashan; and Traditional skills of carpet weaving in Fars.

Other multinational nomination files have been proposed for inscription on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, shared among the countries crossed by the Silk Roads. They include Art of Miniature, Ceremony of Mehrgan, and Crafting and playing the Oud.

Numerous other traditional Iranian arts and forms of knowledge have been exchanged along the Silk Roads – Batik printing, knowledge of navigation in Iranian deserts and crafting of turquoise in Neyshabor. And – eventually – the coveted traditional skills of silk production.

Comments